April 28, 2017 | By Renee Schoof

Louisiana, a state with many chemical plants and refineries to oversee, is wondering how the Trump administration’s proposed cuts of EPA grants to states would hit home.

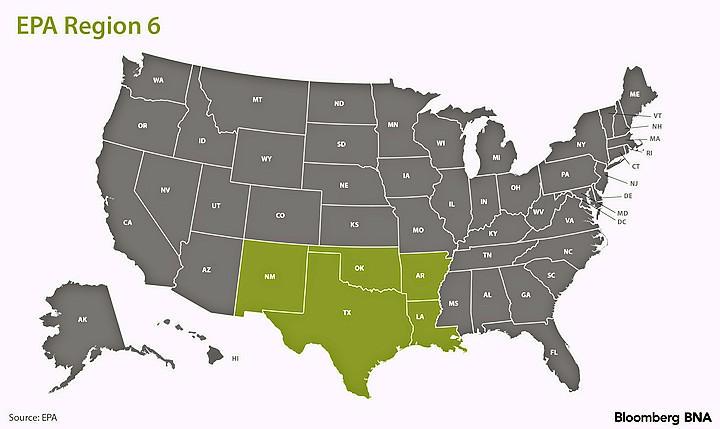

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt’s call for states to take a bigger role in environmental protection comes as the administration also wants to cut the EPA’s budget by 31 percent and the agency’s grants to states by 44 percent. While they await more details on the president’s budget blueprint—and for Congress to make the final decision on funding—states such as Louisiana and its neighbors in Region 6 are considering the changes that could lie ahead.

The Trump administration has been asking states to take greater authority for environmental protection since its beginning, Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality Secretary Chuck Carr Brown said.

“I find that odd,” he told Bloomberg BNA. “You want the states to do more and yet you’re cutting funding. I just don’t see how the two go hand in hand.”

The LDEQ receives about $18 million a year from the EPA, and a cut of nearly $9 million might mean the agency would have fewer people following up on permits, Brown said. If staffing went too low, the state would have to tell the EPA that it was handing back some of its permitting responsibilities, leading to a dual state-federal permitting system that no industry would want, he said.

Oklahoma’s Department of Environmental Quality gets about 30 percent of its funding from federal grants, and also could lose staff if the cuts were large, Deputy Executive Director Jimmy Givens said.

In the area of environmental enforcement, the most immediate impact would be in the number and frequency of inspections, Givens told Bloomberg BNA.

“If you have fewer inspections, you certainly have the potential to have fewer enforcement actions,” he said.

Givens said he’s heard about calls for states to be fuller partners with the EPA, “and we are certainly willing to take our responsibility.” But it’s not clear how more responsibility can be coupled with a decrease in resources, he said.

“That’s what’s perplexing Oklahoma, along with all the other states,” Givens said.

‘Cooperative Federalism’

Pruitt has spoken of “cooperative federalism” in broad terms since his confirmation hearing in January.

“The administrator’s commitment to cooperative federalism means that we want to make sure states are active partners in the implementation, enforcement and development of environmental statutes,” an EPA spokesperson told Bloomberg BNA in response to a question about Pruitt’s approach to enforcement.

The Trump budget blueprint would cut the budget for the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance by $126 million, or 23 percent below the fiscal year 2016 enacted budget.

“OECA’s work is an important part of targeting the most serious water, air and chemical hazards, and we recognize their role in enforcing our environmental laws and building our relationship with states and tribal partners to make sure we are delivering on our shared commitment to a clean and healthy environment,” the spokesperson said.

The Trump blueprint calls for avoiding duplication. EPA would no longer share enforcement authority with states in cases of air, water and other pollution, but would instead provide oversight.

The assistant administrator in charge of OECA throughout the Obama administration, Cynthia Giles, wrote recently that it’s wrong to think that “if the EPA pulls back, the states can pick up the slack.” The reasons, she argued, include: States don’t enforce laws when those harmed by pollution live in another state; many large companies that violate the laws operate in multiple states, and so a single case handled by EPA works better than individual ones; “many states don’t take action to enforce criminal environmental laws”; and some states don’t have the political will to join environmental suits against major companies.

The EPA, however, said Pruitt’s approach would cost less and work better.Pruitt “is committed to leading the EPA in a more effective, more focused, less costly way as we partner with states to fulfill the agency’s core mission,” spokesman J.P. Freiretold Bloomberg BNA. “Washington shouldn’t get in the way of the 50 states across our nation who care about air, land and water.”

Freire also described Pruitt’s approach to environmental enforcement as “stepping up our work alongside the states in assisting stakeholders with compliance to ensure fewer violations.”

“Enforcement will continue, of course, but giving greater compliance assistance at the outset will help protect human health and the environment,” he said.

View From Region 6

States use their general funds and other resources, as well as the grants, to carry out their programs, including compliance and enforcement.

In Louisiana, where federal funds make up about 15 percent of the Department of Environmental Quality’s budget, a 44 percent cut in state grants nonetheless would be significant, Brown said. The LDEQ staff already declined from more than 1,000 to 677 in the past eight years due to budget cuts.

Brown said Louisiana and Texas now are “the leaders from a surveillance and enforcement standpoint.” Together, they have an unusually large amount of industry they must oversee, he said.

Both states have divisions that handle enforcement and compliance, and both put public reports online about the cases they have handled. The Louisiana DEQ, for example, highlighted in its 2016 annual report that its Criminal Investigation Section handled eight criminal cases and that its Office of Compliance issued 1,942 civil enforcement actions.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s Office of Compliance and Enforcement, which handles most of the state’s environmental investigations and notices of violation, has 540 investigators in 16 regional offices for civil complaints. Its enforcement division includes 10 criminal investigators, two attorneys and one manager who handle environmental crimes investigations.

TCEQ officials declined to comment on the president’s budget blueprint because it was not a detailed budget proposal. The details of Trump’s budget proposal are due in May, and then Congress will make funding decisions.

Oklahoma’s Givens said his department received about 30 percent of its funding from federal grants. The money is used broadly for the state’s water, wastewater, hazardous waste and air programs, he said. Enforcement and compliance work is part of the department’s program offices, rather than a separate division. A 44 percent cut in state grants would hamper Oklahoma’s ability to write and implement permits and other functions, as well as its enforcement work, he said.

Oklahoma’s DEQ has a three-person section that handles criminal investigations and refers cases to district attorneys for prosecution, Givens said. Civil cases are handled through an administrative law judge. Like some other states, Oklahoma does not make environmental cases public online.

“I do think the EPA has a role to play, even though the state has the ability to take its own enforcement actions,” Givens said. “They need to ensure, for lack of a better term, that there’s a level playing field across the country. That would be one thing that we would have a particular interest in—to make sure EPA continues that role so there’s not a race to the bottom, either in program implementation or enforcement.”

Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality Director Becky Keogh, speaking on the sidelines of a recent Environmental Council of the States conference, said it was unclear what a budget cut would mean for enforcement because the state also gets funds from fees.

The New Mexico Environment Department did not respond to requests for comment.

Less Money, Less Enforcement?

Karen C. Sokol, an associate professor of law at the Loyola University New Orleans College of Law whose teaching and research interest includes environmental law, said enforcement likely will be scaled back if grants are cut.

The proposed reduction of state grants was “clearly sweeping deregulation, because it guts state powers to do anything,” she said.

Even if the grants were not cut, the overall 31 percent reduction to EPA’s budget would hobble states, according to Sokol. EPA regional offices provide expertise of engineers, scientists and others, as well as help with responses to environmental disasters.

Steven Chester, a former deputy assistant administrator for the EPA Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, said the proposed budget cuts would hit states hard. He also is a former director of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and now is senior counsel at Miller Canfield in Lansing.

The money would have to be made up by raising fees or getting an increase in general funds, neither of which is very likely in most states, Chester said.

“It will vary by state of course, but compliance and enforcement will get chopped and chopped significantly,” he told Bloomberg BNA. “Compliance and enforcement are core activities, don’t get me wrong. But there are other activities you can’t forego,” such as air monitoring and permitting.

In addition, the budget cuts suggest there will be less oversight of states by the EPA, Chester said.

“Each one of these states and each state environmental agency exists within a political environment, and it’s not uncommon for state legislatures to try to pare back what state environmental agencies can do,” he said.

Flexible Spending

The EPA state grants that are subject to the 44 percent reduction proposal were created in a way to give states more flexibility. Some grants were set up in Performance Partnership Agreements, such as the one that Louisiana’s environment department signed with the EPA in 1998. The agreements defined the roles and responsibilities of state environmental agencies and the EPA.

Texas revised its agreement in 2005. Oklahoma’s PPA dates to 1996, but its principles are applicable today, said Erin Hatfield, Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality communications director.

The agreements and Performance Partnership Grants, or block grants from the EPA to the states, are part of an agency system dating to 1995 that spells out the state-EPA partnership.

Today there is more attention to these kinds of agreements and grants because they provide states greater flexibility for how they use federal funds, Environmental Council of the States Executive Director and General Counsel Alexandra Dapolito Dunn said.

ECOS is working to get more types of grants included in the block grant so that states can use the funds as needed, Dunn said.

“Whatever Congress does, it’s likely we are moving to a more lean budget time,” she said. “You have to be flexible when you have fewer dollars.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Renee Schoof in Washington at rschoof@bna.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Larry Pearl at lpearl@bna.com

Copyright © 2017 The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. All Rights Reserved.